Uncle Scrooge discovers cosmic muons

Luigi Marchese, a researcher in the Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, talks about his outreach work with the publisher of an iconic Italian comic series.

Long before he became a physicist analysing data from the CMS detector at CERN and a researcher in the Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics at ETH Zurich, Dr Luigi Marchese was a curious child spending his weekly allowance on the latest issue of Topolino, a popular children's comic series featuring Disney characters published by Panini Comics under a license agreement with The Walt Disney Company.

In the spring of 2020, Marchese kept hearing from relatives in Italy who were stuck at home with their young children in remote schooling, as classrooms turned virtual in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: these challenging conditions, where many parents carried on with their work while supporting their children with schoolwork, led Marchese to think about how to enthuse young ones about science in new and creative ways. Could the comics he read avidly as a child offer a fun format to discover science? His initial contact with the publisher of Topolino led to a successful outreach project that saw him put together a small team of experts who collaborated with the scripters and artists of the popular comic series on three science-themed stories.

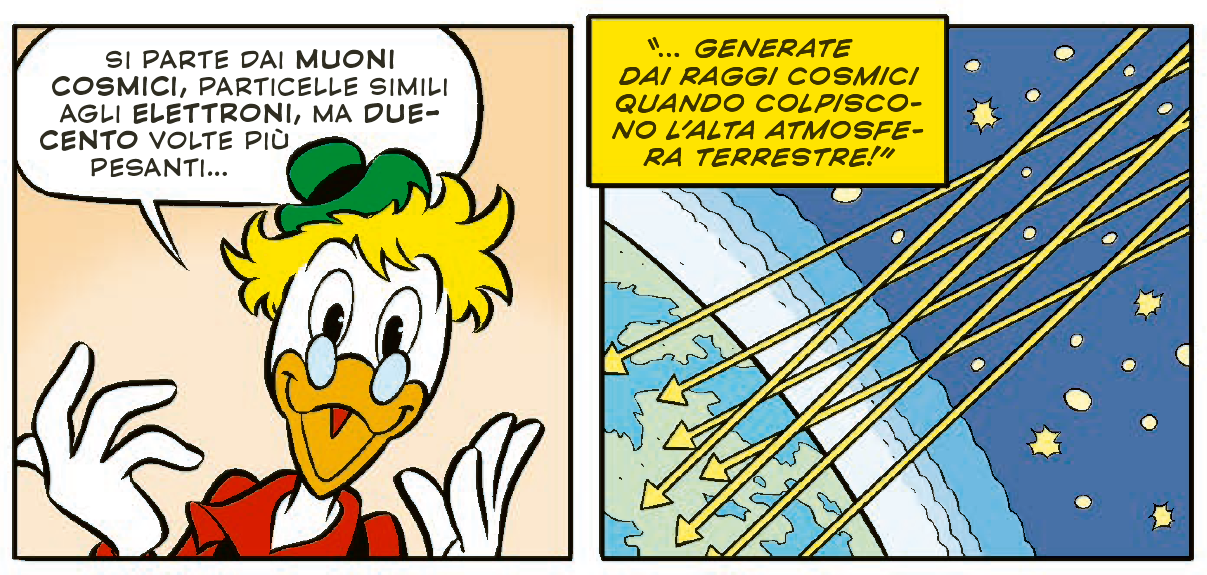

external page The first story, based on the scientific input of Dr Teresa Fornaro, a research scientist in astrobiology at the Italian Astrophysical Observatory (INAF) in Florence, was published in July 2022 and is about the search for life on Mars. external page The second story appeared in the summer of 2023 and is the one to which Marchese contributed most directly. In this story, muon tomography and radiography allow Uncle Scrooge to identify structural weaknesses in the Money Bin that need urgent attention while keeping the Beagle Boys away from his beloved dollars. The story's publication date was chosen to celebrate the Higgs boson's discovery on 4 July 2012 – an achievement where muons played a crucial role. external page The third story, conceived in collaboration with Professor Alessandra Corsi, an astronomer specialised in multi-messenger astronomy based at Texas Tech University in the US, was published on 13 September 2023 with a timing chosen to celebrate the eighth anniversary of the first observation of gravitational waves. The story is about a space journey to a neutron star merger undertaken by greedy Uncle Scrooge, who is ready to travel far and wide to find new sources of gold.

We spoke with Luigi Marchese about his unusual outreach project to find out what he learned and what he would advise fellow researchers to keep in mind when planning similar activities.

How did the collaboration with Panini take shape?

I made the first contact with the publisher in 2020, and in the summer of 2021 the director of Topolino gave me the green light to put together a team of scientific collaborators for working on up to five science-inspired stories. In the autumn of that year, I reached out to several colleagues; once I had experts for all the topics I had initially planned to cover, each of us was assigned a scripter and an artist to develop the story in more detail, that is, choose the characters and refine the plot. Eventually, three stories made it to publication.

Regarding the story to which you directly contributed, what impact do you hope for it? And what compromises did you accept when working on it?

I would be incredibly proud to discover, say 10 to 15 years from now, that at least one young reader of Topolino had developed such a fascination with science after reading my story that he or she became a scientist… Even better if a physicist working at CERN! It would also be my way of giving something back to Topolino, which made me discover science – through characters like inventor Gyro Gearloose and archeologist Arizona Goof – when I was a child.

In terms of compromises, I had to figure out the angular distribution of cosmic muons and imagine the composition of the Money Bin; for the latter, I took inspiration from a proposal to use muon tomography for studying Brunelleschi's dome in Florence. As I risked getting carried away with my calculations, the team of Topolino assigned to work on my story reminded me that we needed to strike a careful compromise: a story that's scientifically accurate and engaging for readers within the constraints of the comic series, where each story is typically 10 to 12 pages long.

The end of my story was the fruit of further compromises. When Uncle Scrooge, Gyro Gearloose and Donald Duck perform the muon radiography of a mountain that supposedly hides a large amount of gold, the outcome of the measurement is instantaneous: this was necessary for narrative purposes, but it's scientifically inaccurate because collecting enough data for a decent radiography would take months. I pointed out this problem and we discussed options; eventually, the team of Topolino suggested that we keep the measurement instantaneous but later reveal it to be a fake, that is, a farce put up by Uncle Scrooge to lure the Beagle Boys away from the Money Bin with the prospect of a treasure even bigger than Scrooge's.

Your story was followed by a short interview article where you described your daily research. The interview closed with an invitation to submit questions to "Topolino" so that you may answer them. What kind of feedback have you received from readers so far?

I was asked about CERN and the role of muons in the discovery of the Higgs boson, which is the type of question I expected. A question by one ten-year-old child was more surprising: she wished to know why we use Greek letters for elementary particles and if there exist Italian letters 'translating' them. It's funny that this question came in, because I insisted that we use the Greek letter µ in the story. I then learned that the initial resistance from the team at Panini came from Greek characters not being part of their standard selection, so that they needed to put in some extra work on the speech balloons.

What is your advice for colleagues wishing to try out similar outreach activities?

My recommendation is – do it! The skills you develop with this kind of outreach are highly transferrable: to be able to present your research in simple and engaging terms is equally useful for working on a comic series and for addressing a funding agency. Also, it's a great way to remind yourself of what makes your research fascinating. Expect this type of project to take time, more time than you may expect. You'll face the challenge of presenting a topic in a way that's accessible to a wide audience, and you'll find yourself reading papers and distilling the complexities of your research topic into more digestible messages. Be ready to accept compromises, but also to keep your point when it's important. If there's a pushback on some aspects, try to understand the motivation – is it just that it departs from the standard or the routine, as was the case with my request for using a Greek letter to correctly indicate the muon? Try to understand how far you can push. Clearly, it helps to find collaborators who are open-minded enough to engage with you, which was my case with the team of Topolino.

I will be publishing an article for CERN about my outreach experience, and there I will provide further details about this project.