How to fail productively

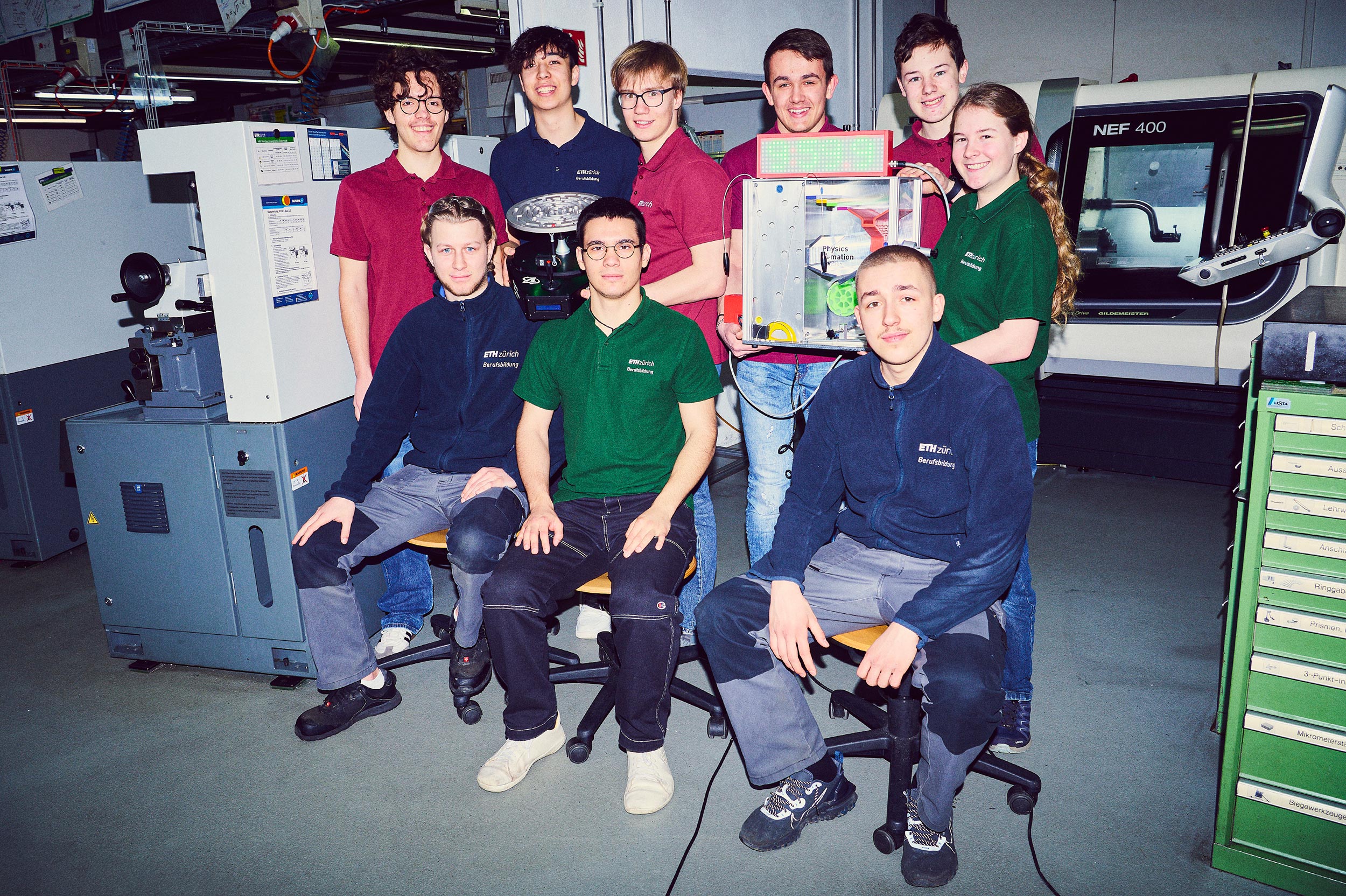

Apprentices from four different professional careers paths within the vocational training programme managed by the Department of Physics had to work in teams to build an interactive exhibition item in the Physics4mation pilot project. They learned how to collaborate with colleagues, carry out interdisciplinary work and handle failure. The Physics4mation project will now be part of the vocational training programme in the physics department.

"It's great to be able to do something different from what you normally do during your training," says future physics lab technician Samira when asked about the Physics4mation project. Together with eight other apprentices from the physics department, she had looked forward to the Physics4mation pilot project. Apprentices were given one task: to work in a team to build a functioning and interactive exhibit item for the Careers Fair in Zurich within a time frame of three months. Importantly, each team member had to come from one of the four professions in which the Department of Physics offers vocational training. Indeed, interdisciplinary collaboration is at the core of the Physics4mation project.

Many ideas

"We quickly came up with lots of ideas," says future physics lab technician Samuele about the brainstorming phase. His team – Team Maze – designed and built an interactive ball maze with time measurement capability: players have to guide the ball through the maze with the help of a joystick. The team also considered a mill game with LEDs to display the score and other features; in fact, Samuele admits that they lost time discussing the details of the later abandoned mill game. Even when they settled on the ball maze, they considered more ideas than they could ultimately develop.

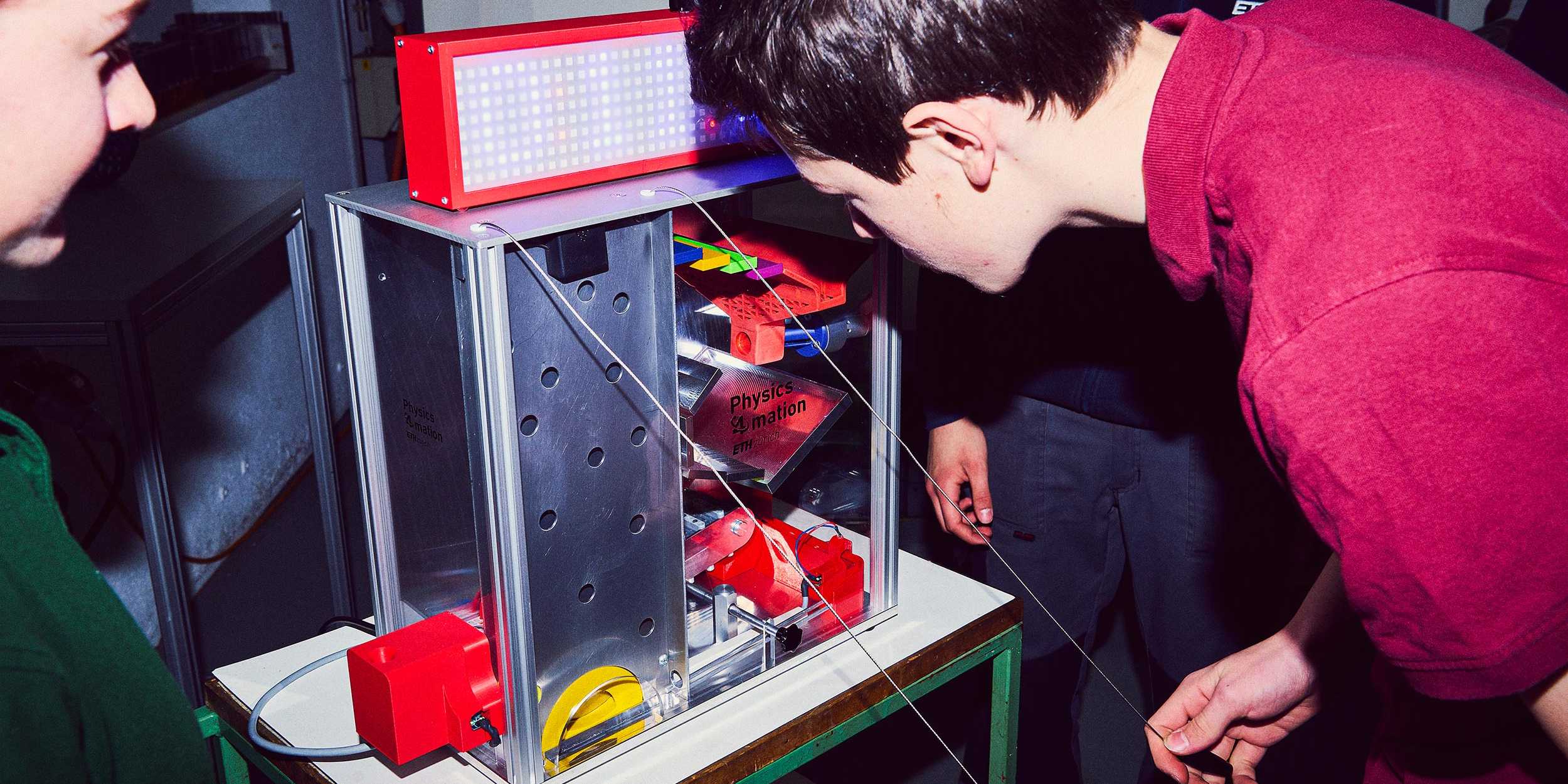

"The project was great and we're very proud of the end product, but we spent too long thinking about what it should look like and what exactly we wanted to do," says future electronics technician Tobias. The other team – Team Marble Run – opted for an interactive marble run with similar time measurement capability. In this case, the ball makes its way from top to bottom and players need to keep it moving. "We had various ideas for the internal modules," says trainee electronics technician Ramon. "We discussed the modules and decided which ones we wanted to install. For example, we thought that a loop would be too big and so ruled out that element," explains Ramon's team member Micha, who also trains as an electronics technician.

Who is in the lead?

In this type of project, it's important to exchange ideas continuously and keep each other informed. Team Marble Run learned this lesson the hard way when their plans had to change retrospectively because the team had not communicated which dimensions the CNC milling machine could process. This cost time and meant that parts needed to be improved until the very end. Samira summarises the learning outcome: "First, clarify whether what you want to realise works given the existing constraints."

Late on in the project, Ramon stepped in as project leader for Team Marble Run. On his initiative, he produced parts using 3D printing and was thus able to make up for some lost time. "Ramon not only took on the role of team leader," says his colleague Micha, "but also drove the project forward with 3D printing." Paul, a future designer from Team Maze, also found himself in a leadership position. "This was my first team project, and taking on the role of group leader taught me a lot," he says. Indeed, a design engineer must be skilled in project management, learning how to keep an eye on the big picture.

The clock is ticking

"Once the design is developed, the item can be fabricated – and then comes the electronics. You can only do the coding once everything is ready," says Tobias, Paul's team member and trainee electronics engineer. As the programming task took longer than expected, the team couldn't keep up with their schedule. Even worse, they found it challenging to follow their agreed plan. All team members learned how to deal with such difficulties.

Apprentices were supposed to work on their project half a day a week for three months. Some of them were able to invest more time and others less, depending on how busy they were with other commitments such as exams. For trainee polymechanic Jeremy, the project came at an unfavourable time as he was on rotation in an office role . This made it difficult for him to carry out tasks in the workshop, so a fellow apprentice from another training centre stepped in and realised the maze panel. "It hurt me that I couldn't mill the maze myself," recalls Jeremy.

As both teams struggled with time management, the deadline was eventually extended by a month. Even that turned out to not be enough. "Even with six months, we probably wouldn't have finished," says Paul. They had all been too ambitious with their plans.

Learning from one another

In Team Maze, Tobias and Lennert were responsible for programming the control system for the maze plate. Being in his first year of training, Tobias had no experience with coding and so Lennert initially took the lead. "I was able to give Tobias some cool programming tasks," he recalls. As they were never able to code together, they wrote down each other's thoughts on paper and left these notes at each other's workstation.

One of the project objectives – that each apprentice also works in other roles than their chosen one – was only partially fulfilled, according to future physics lab technician Samuele. For example, it didn't make sense for an electronics technician to drill a hole; it was more efficient for everyone to work in their own field. Nevertheless, the project made it possible for future design engineer Paul, for example, to spend more time in the workshop and exchange ideas with trainee polymechanic Jeremy. Jeremy told Paul about the limitations of the available machines and what tolerances were realistic. This then simplified the production of the parts for the interactive exhibit item.

Results that matter

All apprentices are proud that, despite the challenges, their teams managed to get the projects to a stage where they only needed a little fine-tuning after they were completed. "It was a good project because the end product is finished and works. This is really cool," says Jeremy. Trainee physics lab technician Samira agrees that the best part in the whole project is the end result. Samuele values how the project enabled him to learn from his team members; Micha reflects that they not only benefited from each other professionally – they also made new friends.

When talking with the apprentices, it's clear that all of them learned about crucial aspects such as project management, communication and network building, and they acquired new specialist knowledge too. Even the fact that not everything always worked smoothly is, at least in retrospect, a most important learning outcome. In this view, the Physics4mation pilot project was a success and has thus secured a permanent place in the vocational training programme offered by the Department of Physics. As an additional good omen, both the marble run and the ball maze survived their baptism of fire at the Careers Fair in November 2023.

Vocational training at D-PHYS

The Department of Physics currently trains apprentices to become EFZ polymechanics, EFZ physics laboratory technicians, EFZ electronics technicians and EFZ design engineers.

To improve further the quality of vocational training at ETH Zurich and facilitate positive learning experiences, Department Coordinator Sebastian Huber asked Christian Richter, full-time vocational trainer for polymechanics EFZ, to look into the future of vocational training programmes in the physics department. Richter then conceived, supervised and evaluated and the Physics4mation project.

The name itself, Physics4mation, was chosen to reflect various aspects of the project – the affiliation to the Department of Physics, the four professional careers for which vocational training is offered, as well as a connection with the idea of formation intended as the process of building a work team.

All apprentices from the four professional career paths will now take part in Physics4mation once during their training. The focus is on interdisciplinary collaboration, network building and project-orientated work. Failure is accepted and considered to be part of the journey, because a successful learning experience is regarded as more relevant than a fully successful project.

Physics4mation ran for the first time in 2023: the feedback received from the apprentices who took part in the pilot project was consistently positive. Still, the evaluation showed that there is room for improvement in individual areas such as the timing of the project throughout the year and the composition of the teams. What's certain is that, from now on, Physics4mation will take place annually.

Further information can be found on the Vocational Training page.

Translated from German by Gaia Donati